This One Script Fixed the “Images Drop In Late” Problem

I run amankumar.ai on Next.js. Pages would load, layouts would appear, and React would do its thing, but something still felt slow.

The problem wasn’t that the page didn’t render.

The problem was this:

That gap, where placeholders sit there and images arrive late, is subtle, but once you notice it, you can’t unsee it. It makes the site feel heavier than it should.

So I stopped guessing and looked at the boring part I’d been ignoring: image payloads.

Why this keeps happening on modern sites (without anyone messing up)

This problem shows up a lot more today, even on well-built sites, and it’s not because people are careless.

A few things are happening at once:

- Design tools export big images by default Posters, UI mockups, and screenshots often come out as large PNGs.

- AI-generated images are heavy by nature High detail, high resolution, no concern for delivery size.

- Frameworks don’t change asset intent Next.js can optimize delivery, but if the source image is huge, it still has to download.

- Image bloat accumulates quietly No errors, no warnings, just slower visual completion over time.

The result is exactly what I was seeing: the page loads, but images arrive last.

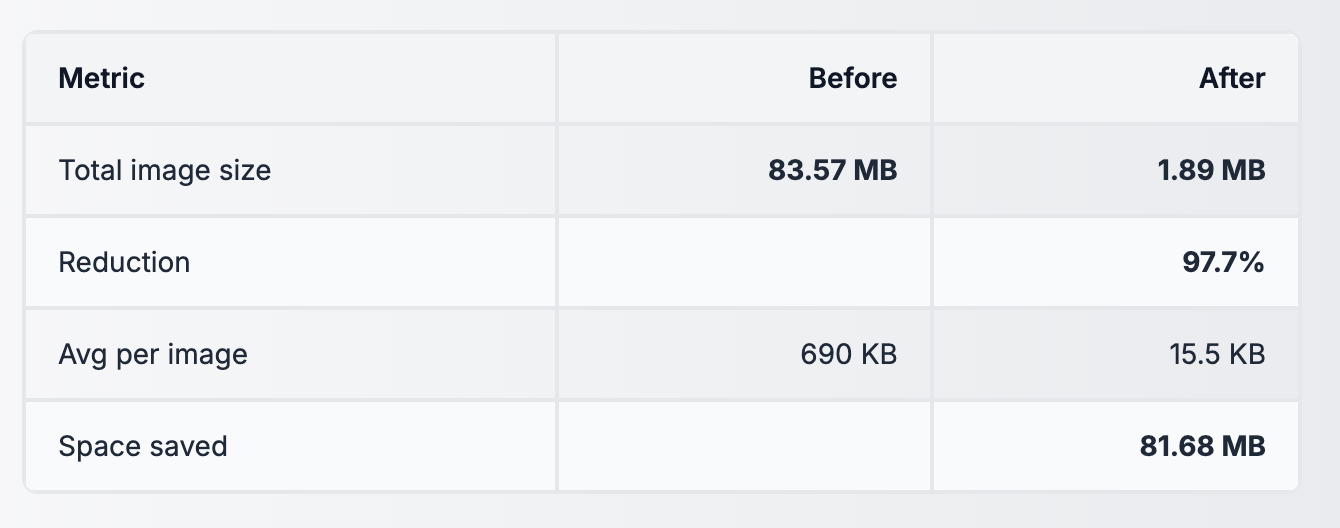

Measuring the problem on amankumar.ai

Before touching anything, I measured the image assets in the repo.

They were a mix of:

- PNGs (most of them)

- some JPG/JPEGs

- different resolutions

- photos, posters, and UI graphics, all mixed together

\

\ This is repo-level image weight, not “every page ships 83 MB.” But it clearly showed the root issue. I was carrying a lot of unnecessary image data, and the browser was paying for it.

The engineering question I cared about

I didn’t want a clever setup. I wanted something:

- repeatable

- boring

- safe for mixed assets

- easy to re-run later

So the real question became:

First principle: pixels matter more than formats

Before debating PNG vs WebP vs AVIF, the biggest issue was pixel count.

If an image is 2400px wide but is never rendered above ~800px, shipping the extra pixels is pure waste.

So I made one hard rule:

This single decision removes a surprising amount of weight.

Image formats: quality vs size (same perceived quality)

Once dimensions are sane, format choice actually matters.

Here’s the practical ranking when comparing images at roughly the same visual quality:

\

\ \ AVIF genuinely compresses better than WebP in many cases.

Why I didn’t standardize on AVIF (yet)

This is important, because AVIF is genuinely impressive.

The reason I didn’t standardize on it is not quality. It’s practical browser support and operational safety.

According to current browser compatibility data:

- AVIF support is good, but not universal

- Some older browsers, embedded webviews, and edge cases still fall back poorly

You can see the current state clearly here: https://caniuse.com/?search=avif

For this project, I didn’t want:

- extra format negotiation

- more fallbacks

- “why didn’t this image load on X device?” debugging

So the decision wasn’t “AVIF is bad.”

It was:

The tricky part: photos vs UI/posters

My repo wasn’t just photos.

It had:

- UI graphics

- posters with text

- logos and illustrations

If you treat everything like a photo and apply lossy compression everywhere, UI assets suffer:

- fuzzy text

- halos around edges

- cheap-looking posters

WebP helped here because it supports both lossy and lossless modes.

The challenge was choosing between them without manual tagging.

The simple rule that worked

I used one clean signal:

- If the image has transparency (alpha), likely UI or graphic, use lossless WebP

- If it’s fully opaque, likely a photo, use lossy WebP (quality ~80)

Is this perfect? No. Is it correct often enough to automate safely? Yes.

That single rule handled mixed assets without human intervention.

Metadata: invisible weight

Many images carry metadata:

- camera EXIF

- editing history

- embedded profiles

None of this helps a webpage load faster or look better.

So I strip metadata unconditionally. Sometimes the savings are small; sometimes they’re large. Either way, it’s free.

Sanity check on a very different repo

To make sure this wasn’t a one-off, I ran the same script, unchanged, on another repo: promptsmint.com, an AI prompts library with only AI-generated images.

Before optimization

- 92 images

- 228.12 MB total

- 2.48 MB per image (avg)

After optimization

- 92 images

- 4.28 MB total

- ~50 KB per image (avg)

Result

- 98.0% reduction

- 223.84 MB saved

Different site. Different content. Same outcome.

That confirmed this wasn’t luck. It was just removing waste.

The script

I packaged the whole pipeline into a single script and hosted it here:

https://gist.github.com/onlyoneaman/cb5dbd36ed351b02e46db13d74e6dbe2

It:

- finds all jpg/jpeg/png/webp

- outputs *-optimized.webp next to originals

- caps size at 800px

- strips metadata

- uses lossless WebP for transparent images

- uses lossy WebP for opaque images

No clever tricks. Just consistent rules.

The actual outcome

I didn’t magically make Next.js faster.

What changed is simpler and more important:

That was the slowness I was noticing, and this fixed it.

Thanks for reading. If you found this useful, you can follow or connect with me here:

x.com linkedin

You May Also Like

The Channel Factories We’ve Been Waiting For

What is the Outlook for Digital Assets in 2026?